A thesis for Out Fitness

I'm in a reflective mood as our studio, Out Fitness Collective, celebrates one year since opening here in Cleveland in October 2022! It has been an terrific learning process and made me exponentially more thoughtful about "fitness."

Also recently, I read an excellent, new book, "Deconstructing the Fitness Industrial Complex," an anthology edited by Justice Roe Williams, Roc Rochon, and Lawrence Koval. I knew it would resonate with my values and also challenge the limits of my knowledge and practices.

After reading the book's 13 essays by 13 exceptional fitness advocates, I believe more strongly that fitness can be a means of greater freedom for all.

I'd like to explore this thesis by reviewing some of the essays and then assess the impact of Out Fitness in its first year.

Definitions and industry context

My thesis above requires some careful definitions, because the American fitness industry has given us a toxic misunderstanding of "fitness."

Anthology editor Justice Roe Williams is a trans, body-positive trainer who founded Fitness4AllBodies, and he explains that our society's institutions, with which we are forced to interact daily, are antithetical to the ideas of fitness, health, or well-being. Many people "historically have been told and shown that their bodies do not belong or cannot exist in these spaces as they are."

"The fitness industry...is a part of a larger industrial complex, which advances a profit-driven relationship that influences and maintains our current social order," says Justice.

Every day, people enter their nearest commercial gym, see posters of toned, young, mostly white athletes, and are asked to complete the gym's standardized exercise, BMI, and body fat assessments. Then they are sold an expensive, impractical workout and diet plan.

I am working to better use my privilege to subvert white supremacy and capitalism in my fitness coaching. Instead of deploying punishing practices that play into people's insecurities, I am learning to prioritize body liberation and harm reduction. So rather than "fitness" being a combination of discomfort and dollars used to attack our bodies' "flawed" differences from one Western beauty ideal...how should we define fitness?

The editors' first challenge to the commercialized idea of "fitness" is asserting that "fitness is for all bodies." I find that challenge powerfully necessary for all of us who grew up with fitness icons of a similar type: Arnold Schwarzenegger, Brad Pitt, Jane Fonda, Jillian Michaels. White, ripped, and (not coincidentally) rich.

Through the lens of "fitness is for all bodies," we counter the typical industry tactic ("fix your broken body") by valuing each body – and our own – exactly as it is. We stop harming our bodies. We develop positive body image and self-esteem. We liberate and care for our bodies. After all, as Justice says, "There is no wrong way to have a body."

I believe my personal definition of affirming fitness aligns with this inherent value in every body:

Affirming fitness leverages an internal belief to change how you treat your body. In that way, it's a reversal of the "fitness" that the industry preaches: treating your body with products to change your internal beliefs.

Is affirming fitness a useful means for greater freedom? I will define freedom this way: freedom is the power to take your own actions. In order to freely take actions of your choosing, you need:

- agency – your personal capacity to make choices

- well-being – physical, mental, and emotional health

- perseverance against oppression – the ability to overcome, often collectively, restraints imposed by others

Because fitness practices, when affirming, can promote all three of these necessities, I believe my thesis is, indeed, supported.

Fitness is a practice of our agency

In the anthology, Lawrence Koval, a writer who critically examines their experience as a fitness instructor, reassigns agency from the fitness industry to the individual:

We should let individuals define "fitness" and their exercises: for pleasure, for social company, for no goal at all, or even for access or survival in a fatphobic, transphobic, ableist society.

This is radically different from my early experiences of fitness defined by others, like being pushed into activities by a gym class teacher or following a "best muscle building exercises" article manufactured by a supplements retailer. It makes sense that my internalized belief that I was "unathletic" damaged my agency to try fitness-related activities for so long.

Justice writes that we should deconstruct our own body image that has been shaped by white supremacy and the capitalist ideal of a "productive citizen." What do we love about who we are, separate from our job, the media, and our internalized doubts? Then, what kinds of movement make us feel connection to what we love about ourselves? When we are (re)connected to our internal identity, Justice says, it is harder for the outside world to mold us and lie to us.

I found strength training connected me to my internal "can-do" attitude, even when that attitude had been diminished by masculinity stereotypes that did not match my experience as a gay man. Feeling stronger and more capable in movements like push, pull, and squat gave me new confidence and a new routine to pursue joyfully. But not everyone needs or wants to be pushing, pulling, and squatting! The numbers on the weights that motivate me may be irrelevant to the movements you enjoy.

This is why it is important for coaches like me to ask a client to define their own fitness. Then I meet them where they are by suggesting appropriate practices. When you repeatedly connect your body and your positive self-image through movement, that is a terrific practice of your agency.

Fitness is part of your well-being

Your well-being should include physical, mental, and emotional health for a high quality of life. The factors in those areas are too numerous for this blog and include many external factors, or social determinants of health, over which you have limited control.

Fitness is just one part of your well-being, but we know it is a part over which you can exercise your agency. As more and more people take on fitness practices from which they'd been excluded, I see lots of exciting essays shared online about their positive experiences. For example, in Colin Crummy's "The Power of Lifting Heavy Things," the author and their interviewees of various ages try weightlifting for physical health and find unexpected mental boosts. Rob Kemp wrote "Is cycling the answer to men's loneliness epidemic?" because he found emotional benefits when the often-solo activity of cycling is done in social groups that accept all skill levels.

In seeking our multifaceted well-being, we must expand "fitness" beyond just our physical ability. Dr. Marcia Dernie is a Haitian American physical therapist and strongwoman with chronic illness, and she explains in "Deconstructing the Fitness Industrial Complex" that our bodies are always on the spectrum of disabilities, seen and unseen. At no time can anyone know our body's capabilities just by looking at it. This, again, counters the fitness industry's idea of a "good" body. We all have internalized ablelism that leads us to characterize our bodies as "bad" instead of inherently good and deserving of care.

Both the mental and emotional aspects of your well-being are supported by exercising and eating. Exercise, in its hundreds of forms, is proven to improve symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression – especially when paired with positive psychology and increased social connectedness. Wholesome eating, among its many benefits, can fuel your exercises and self-care. But there are huge, negative influences on exercising and eating that we must identify and sidestep: ablelism, anti-fat bias, racism, patriarchy. It's no wonder that leaders in fitness-for-well-being are fat, Black women and femmes who are already countering discrimination and diet culture.

Kanoelani A. Patterson is a social worker and powerlifter who survived anti-fat violence beginning at the age of nine. In the anthology, they write about how their family, school, and church all taught them shame about their body, and no one diagnosed the eating disorder they developed.

The most ridiculous part is that no one ever asked me if I was okay or why I wasn't eating. There was no concern for my well-being, and now I know that it was because I was fat. In people's minds, whatever I was doing to 'lose the weight' was good because, to them, fat is bad...

After a breakdown as a young adult, Kanoelani threw away their activity tracker and deleted their diet apps. They incrementally began dancing, cardio training, and weightlifting, and they compassionately listen to their body to continue only the exercises they enjoy. They follow intuitive eating with the same sense of compassion.

I have survived lesser forms of these negative influences, and I have found fitness practices to help with managing my chronic depression. All aspects of my well-being benefit when I care for my body.

Reclaiming fitness for yourself is a powerful step into your well-being, but I hate that it often happens in spite of fitness professions and health institutions. External oppressions are the most insidious factors working against our well-being. I want to further understand how fitness can aid us in collectively dismantling those oppressions.

Fitness is perseverance against oppression

Damali Fraiser testifies that the body is a site of oppression, especially as a Black woman. Therefore, merely caring for your body is perseverance against oppression.

As she describes in the anthology, Damali has experienced loss, sexual assault, and body bias as both "too fat" and "too muscular." She had tried restrictive diets, Weight Watchers, Beachbody's P90X and Insanity, and Muay Thai, but she did not find healing, regardless of her body's varying appearances. She also realized her daughter was growing up while watching her mother strenuously exercise to lose weight. It wasn't until Damali tried and fell in love with kettlebell exercises, even while gaining back previously lost weight, that she began unlearning "fitness" to mean a "better" body.

"Strength training with kettlebells has helped me reconnect within myself in ways that make talking about the oppression in my body necessary and facilitated my healing," says Damali. She established her own kettlebell studio, asserting her place as a Black instructor despite feeling ostracized in her country of Canada. She has hosted conversations in her studio for Black and Indigenous healing, especially concerning pregnancy and infant loss. And after her daughter saw women of all ages, shapes, and sizes lifting, she became a powerlifter at age 14.

"I want to see fitness create freedom in the ways we share movement..." writes Damali. "I want to see fitness as a pure expression of our humanity where compassion leads and joy is close behind."

I believe that joy, when shared with others, can become a powerful force against oppressions. If "affirming fitness" is the practice of believing in your unique body as strong and worthy of your care, then joyful fitness could be a collective mobilization of an affirming fitness community. I think of hundreds of Slow Roll Cleveland cyclists riding noisily through our poorly-designed streets. I think of the Queer Climbing Columbus group claiming space in climbing gyms and outdoor crags to combat LGBTQ+ social isloation.

"Patriarchal whiteness separates us from each other into boxes. The only way to understand this separation is to create spaces for all bodies where we can expose ourselves to each other. This must be done with vulnerability and without white people taking more space where whiteness is the default," says Justice Roe Williams. We must "deconstruct [fitness] by building from the ground up spaces that center and prioritize different values such as fat, queer, BIPOC liberation and disability justice."

Roc Rochon is a cultural worker and founder of Rooted Resistance, a grassroots space and commitment to reimagining movement for queer, trans and nonbinary people. They write in the anthology, "The elitist, Eurocentric field of certified fitness professionals" (in which I participate) "needs people to intervene, going against the commercial motivations of the field and making policy, personnel, and facility changes."

A radically different fitness space, one which invites vulnerability and generates joy, does not exist without careful intentions. As a privileged, white man, I find Justice and Roc's challenges to be scary but important. They motivate me to critique the studio I've created with my neighbors, Out Fitness Collective. Can Out Fitness become an alternative space for fitness that rejects patriarchal whiteness as its default?

Out Fitness and a year of learning

What struck me most about the essayists of "Deconstructing the Fitness Industrial Complex" is how many of them created their own fitness studios. I have now experienced that power of stewarding a space.

My motivation for founding Out Fitness Collective was the lack of affordable and affirming workout space for LGBTQ+ people and their allies. In that regard, Out Fitness' first year was a success, having served 130+ people and ramping up to an average of 35+ workouts per week. Participants are disproportionately LGBTQ+ and indicate similar racial, ethnic, and age demographics as our surrounding neighborhoods. Many participants have told me they would not have a space for their exercise practices otherwise. I also found a leading Google search term for Out Fitness is "women only gym" – which it is every time women claim the space!

Out Fitness truly is a queer and allied community sharing affordable fitness programs and a private studio where we practice strength, endurance, and self-care so we each feel stronger in our own bodies. This is a dream come true for me. I know we still need to do more to center fat, queer, BIPOC liberation and disability justice.

In some ways, we have shaped Out Fitness' physical space to meet our ideals: a safe, private, non-gendered studio, – with a wide range of beginner-friendly (and mostly donated) equipment – located on a major bus line and in an urban, walkable area. In other ways, it falls short: Our building is not wheelchair accessible, our registrations require internet use, and our small spaces limit many forms of exercise and gathering.

How does Out Fitness function within (or without) the fitness industrial complex?

I founded Out Fitness with a diverse cohort of neighbors, all of us with separate primary jobs, so it was never beholden to an existing corporation or our own salaries. That, along with crowdfunding, has allowed tremendous flexibility and experimentation.

Our studio programming consists of small classes and private workouts. Booking private workouts allows individuals or pairs to exercise on their own terms, and this has been our most popular option. It requires a lot of trust and shared responsibility, since participants must follow our rules and take care of our studio without supervision.

Our affordability model is based on low and flexible pricing, usually starting at $6 per workout, and people with more financial means have many opportunities to contribute more. Our modest income now covers our rent, insurance, software, and studio maintenance, and we are paying off our purchased equipment. While we operate within capitalism, no one is getting rich from Out Fitness. Our low barrier of entry allows class instructors to earn income even as attendees pay only what they can. Most of my labor for Out Fitness is unpaid labor of love, and that is one way I redirect capital towards our community members.

Beyond encouraging "strength, endurance, and self-care," Out Fitness has left "fitness" undefined. Participants and class instructors can define their own fitness, so long as they respect each other and the space. (Even just making a cup of tea and sitting is welcome!) There are no diets or supplements sold here. We avoid language defining bodies against dominant images of "fitness." By nature of being a private studio, our participants can exercise without seeing (or being seen by) people who play into fitness stereotypes at commercial gyms.

Our intimate classes have included yoga, low-impact exercise, self-defense, and meditation – all beginner-friendly and taught by our community members. I recently participated in an Intuitive Movement Workshop, led by my neighbor, and it really helped me understand how to listen to my body and sense joy in movements. My own class, Stength for Absolute Beginners, continues to be our most popular, and I take this responsibility seriously. I continue to evolve the class to allow each person to experience agency, without judgment, while they try new movements and equipment.

I've been inspired by another declaration written by Justice Roe Williams: Trainers must "be a sword against the fitness-industrial complex while shielding our clients from toxic fitness culture." I am proud of the Out Fitness shield that protects our participants. I am working to subvert the fitness industry as a personal trainer by inviting my clients to define fitness for themselves and set sustainable goals towards well-being instead of body standards. While I think my approach does help counter oppressions, I am still practicing discussing oppression with clients and class participants.

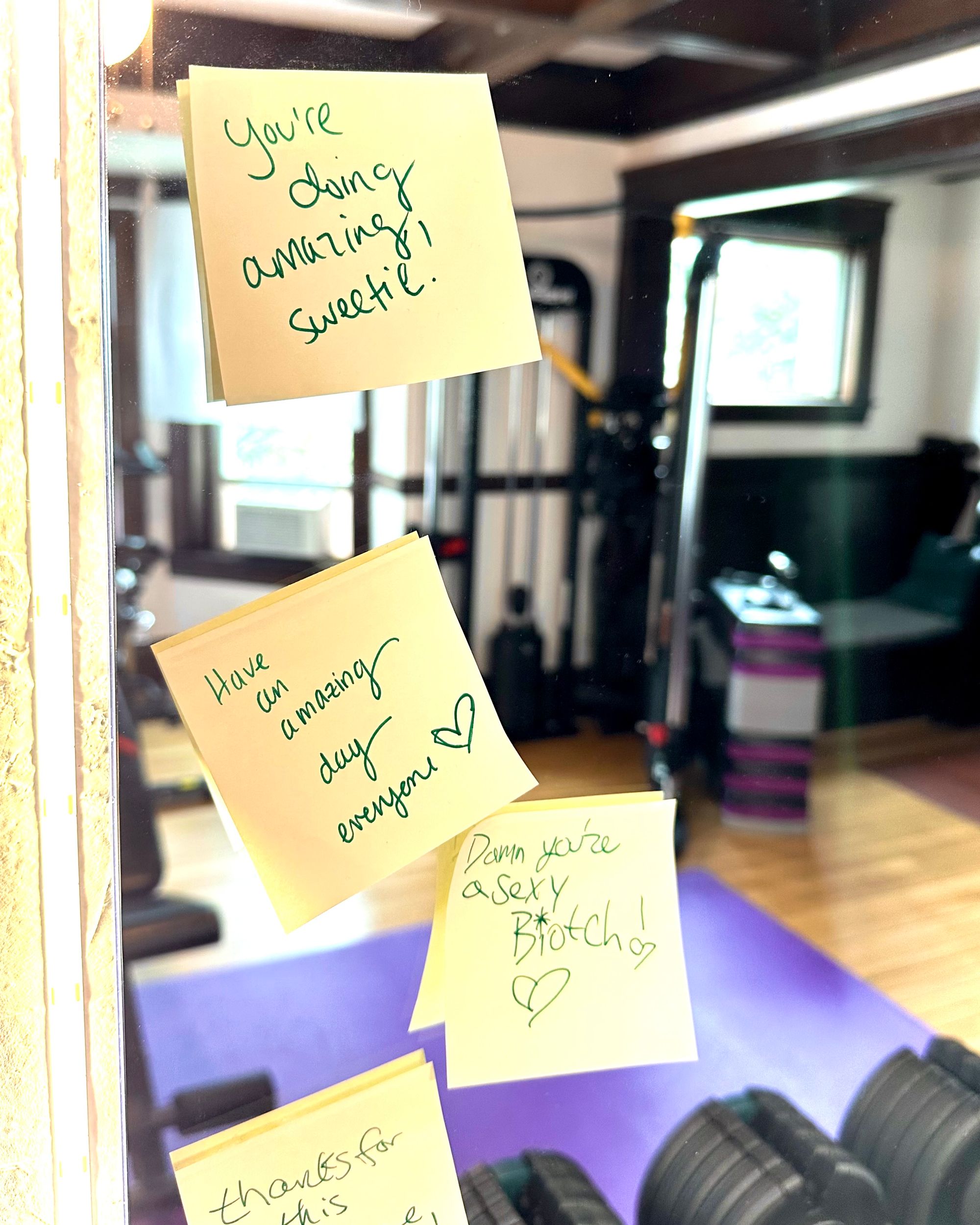

As a community, Out Fitness has certainly grown, and several people have made new friendships (me included)! One tight group of friends comes to Out Fitness to follow YouTube dance workouts together. Yet our social connections as a community are relatively weak, as most people work out here alone. I do think we have shared values as a community, and increasing opportunities for social connection could make us a powerful group! So far, half a dozen of us have attended small socials or gone "Out on the town" to other fitness activities like rowing classes. I'm looking for more ways to foster our community's connections, especially without centering myself. Right now my favorite interactions are the asynchronous affirmations people leave on sticky notes!

Future of Out Fitness

All the joy people have already found in their practices here is invaluable, and that motivates me to continue stewarding Out Fitness for Year 2 and the future. Beyond our inclusivity efforts, we need to foster stronger connections within our diverse community. I see in our future a larger, more accessible space where we can safely practice more forms of exercise and experiences like group discussions. (Perhaps we could even become an exchange point for our community's abundance of exercise equipment, recipes, or plants.) I will be pushing away the dominance of white patriarchy, which harms me, too, by redirecting attention from myself. I will invite more partners of many life experiences to grow upon and shape Out Fitness.

With gratitude

I must conclude with my sincere thanks. Friends, family, and neighbors have directly invested their time and money in me and Out Fitness. This has been incredibly fulfilling work for me. I also feel immensely privileged to be able to read "Deconstructing the Fitness Industrial Complex" and find actions to take from it!

Anyone can purchase some dumbbells or rent a space; it's our values-based community that makes participating in fitness worthwhile. While my thesis may be lofty, I believe the intention of bringing about greater freedom is what will guide Out Fitness to benefit each of us.

If this reflection was valuable to you, I encourage you to purchase "Deconstructing the Fitness Industrial Complex" or donate any amount to Fitness4AllBodies.