"No brain, no gain" — the psychology behind your workouts

I was as surprised as anyone when strength training became my hobby. My experiences with exercise had been varied, but I always remembered the negative ones and thought of myself as "unathletic."

Overcoming that mental trap required rethinking my identity and finding the right motivations. It's a squishy process. Psychology can help.

Like many of us, my anxieties around sports and exercise began in gym class. In a competitive and insensitive environment, it was my below-average coordination and internalized homophobia that torpedoed my athletic confidence. For some classmates, it was their body size. Or it was a bully sneering at them. (Dodgeball seemed designed to multiply all these factors at once.)

Thanks to P.E., I never even considered trying out for football, baseball, soccer, or basketball. In my later school years, I ran cross country and then moved on to marching band, both of which were more supportive and risk-averse. Many other students stopped putting themselves in physically vulnerable activities altogether.

And unlike my women friends, I was mostly spared from our society's pernicious reduction of my value down to my body.

As Danielle Friedman states in How To Reframe Your Relationship With Exercise:

"When Jane Fonda told her ‘80s aerobics disciples that 'discipline is liberation,' she cemented the message that, for women, freedom came from treating our bodies like projects to be worked on forever."

For those of us who didn't feel welcomed or naturally talented in mainstream sports, physical activity often became a chore. For me, tossing a football (poorly) was the entry fee to being included in the neighbors' pool party. For countless others, pounding on a treadmill was an obligation in response to repeated "suggestions" from beauty magazines or doctors.

It's a quiet, national tragedy that negative psychology around exercise is yet another product of oppressive systems (patriarchy, fatphobia, racism, gender normativity).

Exercise has so many objective benefits when we separate the biological effects from the societal obstacles. Exercise triggers some fabulous mechanisms in our bodies:

- decreases in stress hormones like cortisol and epinephrine and increases in dopamine and serotonin

- improvement in symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression and a reduction in all-cause mortality risk

- increased sense of social connectedness (when exercising or sharing accomplishments with others)

But there's an important condition here:

"When we work out mostly because we feel like we should, the guilt and pressure can interfere with the body’s reward system, blunting some of the positive effects, according to Kelly McGonigal, Ph.D., a psychologist at Stanford University and the author of The Joy of Movement."

To reap the full health benefits of exercise, you exercise because you want to, not because you have to. For me, that was a pretty steep hurdle to overcome.

Some positive psychology can be the counteragent to those feelings of guilt, obligation, or fear.

One tactic is to consider the huge variety of exercise options and environments. Don't accept limits for yourself when qualifying the kinds of movement you enjoy as "exercise." I was mortified when I attempted a tennis serve in public, but at home I continued dominating my siblings at Wii tennis. And when our mother forced us outdoors, we'd create inane obstacle courses or games, like throwing a kickball over the roof. Exercise!

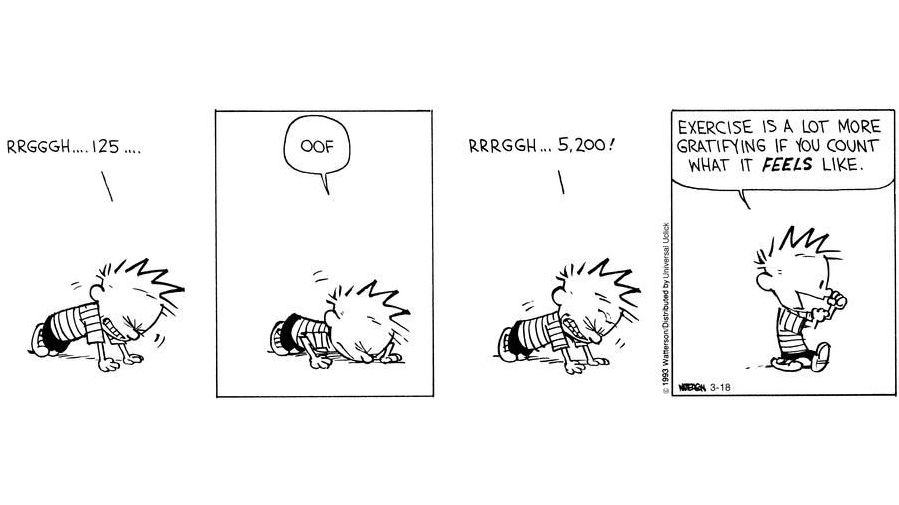

Another tactic is to focus on how you feel during an activity rather than how you look or score. This might require replacing culturally typical marks of performance, like defeating an opponent or waking up with soreness, with this question: Do I feel happier, stronger, more capable? Or even: Do I appreciate my body just for trying its best? This focus may take the form of mindfulness, like observing your body's sensations without judgment during a yoga pose.

By combining these two tactics, you can keep trying different exercises in different environments until you discover ones that feel fulfilling.

And yet, even if you have the time and resources to try new activities, finding the motivation to return to them can be tough.

Within the self-determination theory of human psychology, studies have found that adopting a new exercise is likely influenced by two autonomous forms of extrinsic motivation:

- identified regulation ("I believe exercise is important.")

- integrated regulation ( "I am someone who exercises.")

While these motivations might be initiated by external influences, they can be internalized, which is the best predictor of long-term adherence. There are three needed conditions for intrinsic motivation:

- autonomy (freedom of choice)

- competence (ability to perform)

- relatedness (relationships with other people)

With the addition of self-determination theory as a third tactic, your journey along this motivation path might look something like this:

I wasn't drawn to exercise as a kid because I was asthmatic. But I always read about the health benefits of working out, so I knew exercise was important. I recently tried a nearby dance class, and after only two weeks, I can't stop talking about the moves I've learned. I even made a couple of friends there, so I guess I'm a "dance class person" now.

This individual is much more likely to stick with their chosen exercise than someone who joins the same class solely to claim their employer's health insurance credit.

Here's another hypothetical example:

I played baseball in high school but stopped when I injured my shoulder. I wanted to keep being athletic like my brother, so in college I made up my own crazy drills, like running up the steepest hill on campus. Then my roommate talked me into a Tough Mudder event. I didn't tell anyone else I was signed up in case I failed to finish the course, and it turned out to be the hardest thing I've ever done. But that "Mudder Legion" headband is now my prized possession, and we're training for our fifth Tough Mudder soon.

It sounds cliché, but believing that an exercise is "for you" and doing it "for yourself" can radically change your experience.

This is why I'm so passionate about my studio, Out Fitness, for LGBTQ+ and allied people to try new exercises in a private space to discover feeling stronger. My thesis is a community studio that enables the freedom to care for ourselves without toxic fitness culture.

If you're curious about an exercise but don't feel it's "for you," try interrogating that assumption. Maybe your past experiences with exercise were in the wrong environments. Or maybe you hold a limiting belief about yourself. For example, if you don't identify as an athlete...then a powerful mental hack might be expanding your definition of athleticism.

Ross Tucker, a sports scientist for World Rugby, believes if you have performance aspirations, then you're an athlete. Are you trying squats to keep up with your growing baby so you can hold her more easily? That's damn athletic.

In an article by Ian McMahan, sports psychologist Jim Afremow said:

“The reason why I think embracing an athletic identity is important for us is it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Our thoughts and beliefs about ourselves lead to expectations about our actions. And then those lead to those behaviors and actions, and that reinforces itself where it bolsters our sense of being an athlete.”

I stumbled my way into this virtuous cycle. Finding my athletic identity and sustained motivation looked something like this:

- I tried going to gyms off and on because I wanted to "look good" and to finally be good at something physical. I ended up at a community fitness center (covered by my health insurance) where I could fumble with machines and weights without too much scrutiny.

- Once I experienced how weights became easier to lift after several workouts, that lit up the competence part of my brain. I began reading online articles about weightlifting techniques, and that kept me going back to try them.

- After some time, I could truthfully state that "I go to the gym," a new identity that surprised/impressed my friends. Their encouragement and the many positive feedback loops of strength training kept me going.

- Three years later, as I was newly vegan, my neighbors took me to see The Game Changers, a propaganda documentary about plant-based athletes. What struck me most was seeing athletes doing what I was doing: training regularly and eating to feel their best.

- When a couple people asked me for workout advice, I became interested in turning my passion outward and becoming a personal trainer to provide a helpful relationship for others' fitness discoveries.

Now, when I'm getting to know a client's goals, we discuss their initial motivations, any past experiences behind their exercise preferences, and assumptions they have about themselves. Whenever possible, we set smaller goals that provide autonomy, competence, and relatedness. I then facilitate new exercise experiences they might enjoy until we find the ones that allow them to feel validated and believe in themselves.

It's been fascinating to me to learn the wide variety of thoughts people hold about exercise. And yet, a few psychology techniques might unlock new ways of thinking and exercising for each of us.

![Book recommendations [updated]](/content/images/size/w750/2024/07/Screenshot-2024-07-08-at-8.01.24-PM.jpg)